Power

Whenever we ask questions about community influence, people start talking about power and it is one of those topics of conversation that could go on forever. Our challenge is to capture some of these conversations and provide enough information to get you thinking about power in terms of influence and, if you are already doing that, to get you thinking about what you need to consider when working with any of the frameworks in the Axis of Influence series, or thinking about community development and community empwoerment.

The very nature of community influence suggests that power is at play: there are power relationships to consider – within and between groups, organisations and sectors; some people have more power in different situations than others and people want (or need) to find ways to hang onto their power.

Thinking about power?

Some people think about power as a finite resource – some have more of it than others and it needs to be seized, given away or shared

Others think about power as something which grows from within – finding common ground and collective strengths to build on

Recognising different interpretations can help to explain the different ways people go about addressing power imbalances.

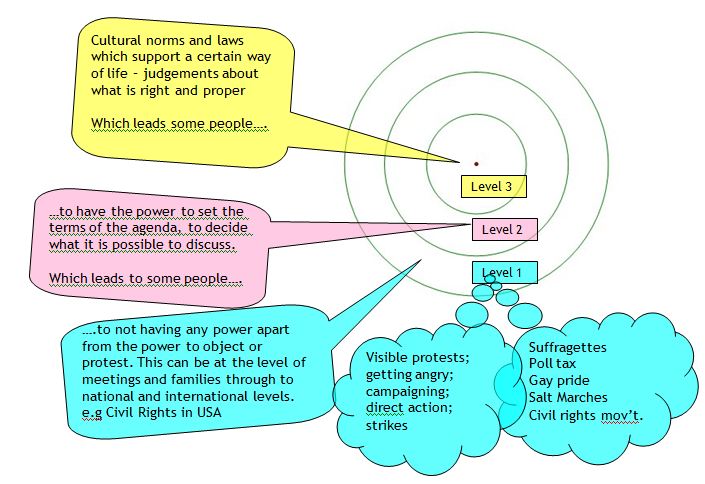

We have found that Steven Lukes’ work on the ‘three dimensions of power’ to be really helpful in making sense of why power is not distributed equally in society – and that this unequal distribution has clear patterns which we can all relate to. (Lukes, Power: A radical view (1974) The central concern of his book is ‘How do the powerful secure the compliance of those they dominate?)

Some people (or groups of people) clearly have more power than others – they have more of this ‘ability to shape outcomes’. It is also useful to recognise that people sometimes do not recognise the power they have – individuals themselves don’t necessarily feel powerful.

Those who have the power to set the agenda need only whisper, whilst those with least power need to make themselves heard. Those people or groups we see campaigning, getting angry or taking direct action are generally those with least power in any given situation – otherwise they would not have to make a fuss or organise to get their voice heard and taken account of.

These ideas are linked closely to Bourdieu’s and Coleman’s theories of social capital: social capital as social relationships or networks which provide access to resources and thereby confer advantage.

So, this framework helps us to analyse who has more or less power and helps us to understand how those with power get to keep it. It also links directly into the equalities agenda as we can say that those people who are able bodied, heterosexual, male, white and upper class generally have more power.

In our society this is generally seen as normal – and this very idea of what is normal keeps the whole system going and makes it hard to recognise.

We live our lives mostly unaware of the power differentials that shape our lives and opportunities – until something happens to bring it our attention. Direct experience of power inequalities though stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination is a brutal way to bring it to attention.